Organic farming has been called a myth and a hoax by academics in the span of about 60 years.

Yet people are buying organic products more than ever, according to a 2015 FiBL-IFOAM report. Retails prices might catch a customer’s eye first. However, the price between organic and non organic products amounts to a few cents difference compared to the price a grower gets for ingredients, according to organic farmer Bart Hall.

You might see a $6 box of organic corn flakes, which an organic grower might get 7 or 8 cents for the ingredients, he said. At the same time, he said non-organic growers might get 5 or 6 cents from a $3 box of non-organic corn flakes.

“The biggest problem in organic right now is that corporate processors are liquidating the market value of the term organic that many of us have spent a generation or more trying to develop through hard work, hard study and creative approaches,” he said.

The “certified organic by” line on a label tells more about a product’s integrity. Though certifiers have to uphold the same organic rules, not all certifiers are created equal. The meeting that made one of the largest, international organic certifiers happened in a small farm house in Quebec on a snowy day in February 1985, Bart recalled.

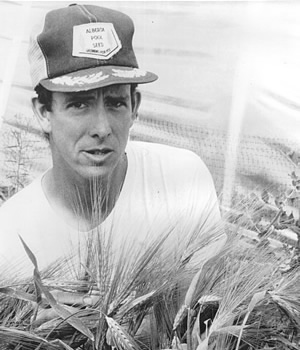

Bart was a broccoli farmer in Quebec at the time when he was invited to Russell Pocock’s farm, southeast of Sherbrooke. A handful of people met there and hashed out an idea for an organization that later would be named the Organic Crop Improvement Association.

They were desperate to find an agronomist sympathetic to organics, Bart said. His practical experience and education set him up to create some of the first international organic standards. He would inspect 750,000 acres and several hundred processors to those standards in seven countries, and find love along the way.

Bart came from a family of farmers who grew vegetables in 1868 near Richmond, Va., with a motto, “‘Sell it or smell it.’ And if you’ve ever been around rotten potatoes,” he said. “You know what I mean.”

His family moved to Canada where Bart’s grandfather taught him how to make compost and grow things organically, he said. He later received degrees in geology and geochemistry, studied two years in agronomy and plant breeding and went on to pursue a doctorate in soil chemistry and agronomy at the University of Guelph and McGill, two leading agriculture schools in eastern Canada, he said.

He said he proposed a dissertation on phosphate fertilizers because they seemed to be inefficient, over applied and could end up in rivers. He said he wanted to look at different forms of the phosphate fertilizers in three soil types, three regions and three major crop rotations, to see the most effective form for soil and bioavailability in a crop. The topic turned sour.

“We can’t really support you in this research,” he remembered the dissertation committee chair said. “It’s terminal research.”

Bart said he replied, “Terminal, like you think it’s going to kill me?”

“Terminal, like it’s not going to lead to other research,” he said the chair replied. “Really, the only people who would be interested in the research would be farmers.”

Bart remembered he said, “Who do you think you’re here for?” Walking out of the room and ending his involvement in academia.

“It became clear to me I was somebody who had to put my brain to work through my hands,” he said, “not some academic setting.”

His education to that point proved valuable to farmers as organics become more popular. He recounted how OCIA grew since its first meeting: Jerzy Przytyk worked with a coffee grower in Peru; Tom Harding was connected with others in Guatemala; hot summers in Latin America eventually burned up vegetable crops and that was when Bart’s crops came in. He was tasked with writing internationally appropriate standards in English, French and Spanish.

“They were done before the snow melted,” he said, “and away we went.”

Farmers could use the same certification, seal, program and standard so customers would have seamless certification for things like broccoli, romaine lettuce and coffee.

The group had another 1985 meeting in Albany, N.Y., with various areas represented. People looked at Bart because he was fluent in several languages, he had an agronomic background, he was a farmer and he recalled the saying, “You’re it, guy. We want you to be our first president.”

What Bart did in 1987 was “crucially important,” he said. Other certifiers had the same man or woman leading them and weren’t consistently farmer-owned and controlled, he said. Bart stepped aside as president and gradually handed off his responsibilities. He became OCIA’s secretary for two years and spent four to five years on the organization’s International Standards Committee.

OCIA International incorporated in Pennsylvania in 1988 and by the next year its directory reportedly listed 6,000 certified operations across the Americas.

Bart continued inspecting organic farms and training new inspectors. He was a founding member of the International Organic Inspectors Association in 1991 in Baltimore, according to Margaret Scoles, executive director of IOIA. Other certifiers were nervous because she said they thought it was an association of OCIA as many people in it were OCIA inspectors, including Scoles, starting in 1988. The “I” in IOIA was “Independent” when Bart and Scoles were among 27 people attending its first meeting.

Soil building brought the people and the certification system together.

“The soil is where the inspector can make such a difference in the discussion with the farmer because that’s the thing the certifiers can’t really see,” Scoles said.

Scoles remembered applying organic rules about soil fertility while inspecting farmers in an OCIA chapter in Nebraska who mostly rotated wheat and fallow in their fields. She said she told the farmers that this crop rotation would eventually mine minerals from the soil. She expected she wouldn’t be welcome to inspect those farmers again.

Then she got a note from the chapter’s treasurer at Christmas that the chapter passed a rule saying one fourth of a farm’s crop production had to be in a green manure. The chapter did accept her as an inspector again. Most chapters used Scoles’ input, she said. They built their soil and working relationships.

Inspecting led Bart to build a personal relationship too, as he happened to be at a few of the same agricultural events as Margit Kaltenekker. Margit was looking at adding organic inspecting as another tool in her bag, she said. She was familiar with OCIA as she worked under Richard DeWilde who started OCIA’s Wisconsin 1 chapter. Bart taught the first OCIA inspector training in Pennsylvania that Margit attended. Bart later sent postcards to her and other colleagues while inspecting in Bolivia.

“She answered with a letter, and thus it began,” Bart said. “Back and forth, letters for months, and colleagues became friends. Eventually, through the letters, we actually fell in love with each other.”

Margit said Bart used to joke he’d get marriage proposals in Canada because his carrots were so good. She soon added Hall to her last name. They inspected a lot of farms and traveled a lot of back roads, she said, including every back road in northeast Kansas. The state was a candidate for them to get their own farm.

They looked at what they could afford and she said they thought, “Are we supposed to go to Kansas? Just give us a sign, Lord.”

Then their friends started calling, “We’d love to have you as neighbors. Why don’t you come to Kansas?”

They settled at a farm near Lawrence, Kan., in December 1998, Margit said. The farm had find, silt-sandy-loam bottomland, Bart said. Still, the land was row cropped “pretty hard” before they got it so they planted alfalfa to heal it, he said. Bart saw spring wind in Kansas stir up dust in a neighbor’s field with crops only to fall apart when it got to their farm where organic matter helped particles clump and aggregate, he said.

Crop improvement and primarily soil management are competitive advantages for farmers and he said they have to take every advantage they can get. Margit said she thought OCIA’s commitment to crop improvement was one reason they both stayed with the organization.

Thirty years since the first OCIA meeting, Bart is an OCIA certified organic farmer. Margit and Bart are raising fruits and vegetables at the Prairie Star Farm, along with the next generation: they have a four-year old daughter Roosmarijn.

“The most important crop we raise on an organic farm is our children and we need to remember that,” Bart said.

CONTACT

Date Published: September 22, 2015

Author/Title: Demetria Stephens

E-Mail: sandnuri@gmail.com

Phone: (785) 678-2475

Address: 2852 F Lane

Jennings, KS 67643